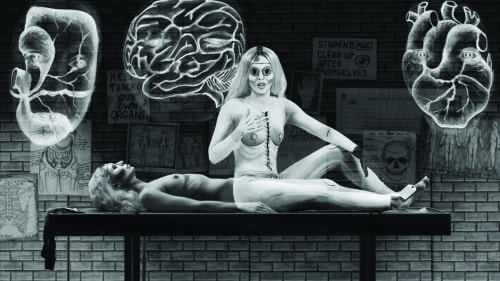

Mary Reid Kelley and Patrick Kelley's short film "This is Offal" is a belly-laugh funny meditation on the divide of the body and soul after death. In it, the body of a woman who jumped off a bridge and drowned lies on the table of a pathologist, who, a bit dejected and pessimistic, describes the death as a suicide by drowning. Meanwhile, the woman's disembodied body parts—liver, brain, heart, foot, hand, and body, all played by Reid Kelley—come to afterlife and begin giving one another the business, fighting like contentious siblings at a holiday meal.

Everything speaks in rhymed lines that sometimes find the sing-song cadence of a bawdy limerick. At one point, the liver blames the brain for the body's death with lines that deliver a spiteful microaggression about depression: "You're the thinker! But I know what wrecked us / Your brainwaves, your ideas, your judgement lapses / Your nervous neurons and your sad synapses!"

The short film is inspired by 19th-century English poet Thomas Hood's "The Bridge of Sighs," about a woman whose body is pulled from the Thames. Poetry from the 19th century—along with early cinema, comics, and cartoons, and the history of ideas—are some of the many sly allusions Kelley and Reid Kelley pack into their accessibly absurd, endlessly imaginative, and philosophically potent works. The two are the 2017-2018 Artists in Residence at the Johns Hopkins Center for Advanced Media Studies, and "Offal" is one of two films included in the exhibition We Are Ghosts, which runs through Aug. 19 at the Baltimore Museum of Art.

Curated by Kristen Hileman, the BMA's senior curator of contemporary art, the exhibit also includes the film "In the Body of the Sturgeon." In it, Kelley and Reid Kelley imagine life aboard a U.S. submarine patrolling the Pacific theater in the waning days of World War II. It moves through scenes that are as claustrophobic as Das Boot, as playful as cartoons, as visually arresting as 1920s cinema, and as movingly human as a favorite anti-war song. The film is a co-commission between the Tate Liverpool, where the exhibition debuted last year, and the BMA in partnership with the Center for Advanced Media Studies.

Tonight, the exhibit curator will host the filmmakers in a conversation taking place at the Baltimore Museum of Art at 6 p.m. In advance of the artist talk, theHub caught up with Kelley and Reid Kelley to talk about their visual language, wordplay, and the politics of language.

Where do you draw some of your visual ideas from, in terms of character, costumes, and sets? In these two films some of your ideas bring to mind comics, the economy of Bread and Puppet Theater sets and costumes, and, for some reason, Czech new wave cinema.

Mary Reid Kelley: Comics have long been an inspiration, particularly people like George Herriman. Also early cartoons, like early Disney cartoons.

Patrick Kelley: The early comics thing started when we started doing projects together, which were all taking place around roughly World War I. Connected to that, we were also thinking about early cinema—the earliest cinema, where it really didn't have much of its own language outside theater, this idea of pointing the camera at a stage. The stage itself was also very much apparent and kind of crudely made, like a theater set. We were really appreciating that aspect of the viewer being aware of that theatricality, and that aspect continues [in the work] as we moved out of that time period and into the later stuff. We were thinking about German Expressionist films and really dramatic lighting.

Does your use of black and white for your films come from a similar interest in early cinema? Do you appreciate that black and white imagery is already abstracted from taking place right now, indicative of a time period that is somewhere and sometime else?

MRK: It's an immediate signal that you're not in a realism-based world, that it's a constructed world, a provisional world, one where people talk in rhyme, not in a metered speech, and where areas of the body, the realism of the eye and the mouth are blocked off, and you get the picture of the lips through the lipstick. You get the covering of the eyes, replaced with, in the character of the Ghost [in "This is Offal"], with the symbol of the coin, the symbol of the dead figure.

Did early cinema influence the look and editing in the film "In the Body of the Sturgeon," where the speed and movement sometimes feel like frames are skipping?

PK: The main time editing difference in "Sturgeon" is that when Mary wrote the script, which is a mosaic text put together from a pre-existing poem—"The Song of Hiawatha" by Longfellow—right away we decided that it would have to be visually in sync with the breaks in the text. That's when we decided we'd do the jump cuts for every break in the mosaic text. It flows, but we did multiple takes for every scene and pieced them back together.

Last week I read your Art in America article about Wipers Times, the darkly comic First World War journal made by British soldiers in the trenches in Belgium. I appreciated your discussion of how the soldiers use language as a medium for powerful satire. You use a great deal of playful wit, puns, and other wordplay in your scripts, which we don't encounter as much in contemporary written language. Could you talk about your interest in the language and wordplay of previous eras?

MRK: There was a lot of wordplay and wit contained in a more print-based society and culture at the beginning of the 20th century, in things like poetry and also things like music halls. It wasn't just found in books of avant-garde poetry—rhyme and wordplay existed across the culture, in the music halls that were frequented by all classes. Now, I think a lot of that wit and word play is still there [in our culture], a lot of it has gone into music like rap, where rhyming and wordplay, making plays on names of things and brands. That's very integral to expressing the viewpoints and the status of the speakers. It's still there, it's just morphed.

Do you think there is a political element to using wordplay to explore ideas?

MRK: There absolutely is. I would say it's a meta-historical position about language itself and about the trustworthiness of language, particularly how we cannot build language on our own, how language is a shared construction that goes on in real time between speakers through time, so you can speak historically, you can listen historically by opening an old book of poems or protest songs. But we're also having to use it right now as an active tool to transmit ideas. So it's a tool for art and it's a tool for the most basic communication. But it's a creation that we have to actively construct constantly. I like it for that reason because it's a creation of humanity that is so ubiquitous that we often forget that it is not a given, and it doesn't exist a priori to us opening our mouths with an intention in mind.

I like that you bring up the relationship between agency and language. In "This is Offal," just by having the woman's individual organs speak, you're introducing ideas about how the parts of the body relate to each other, ideas that in medical science have evolved over time. So how does language shape our own ideas about or our relationship with history?

MRK: I'm not totally sure this is a direct answer to your question, but the idea to dismember the body and have the chorus be composed of the speaking body parts was inspired by a 17th-century Andrew Marvel poem called "A Dialogue Between the Soul and the Body." In it the soul and the body are arguing about who has the worst life—which is harder and which is the worst job of being human? Being the soul and having to be in charge of morality, which is constantly decrepit? Or being the actual body and suffering the pains and humiliations of being literally embodied.

PK: This makes me think of that idea of the tyranny of the present, how the study of history liberates you from presentism.

MRK: We call it the provincialism of the present, where everything is about now and the past is full of ghosts in the closet and nothing is to be gained from studying the past. And that's essentially a form of time-based provincialism, to think everything is happening now or will happen in the future. And that's not how we want to think.

— Bret McCabe